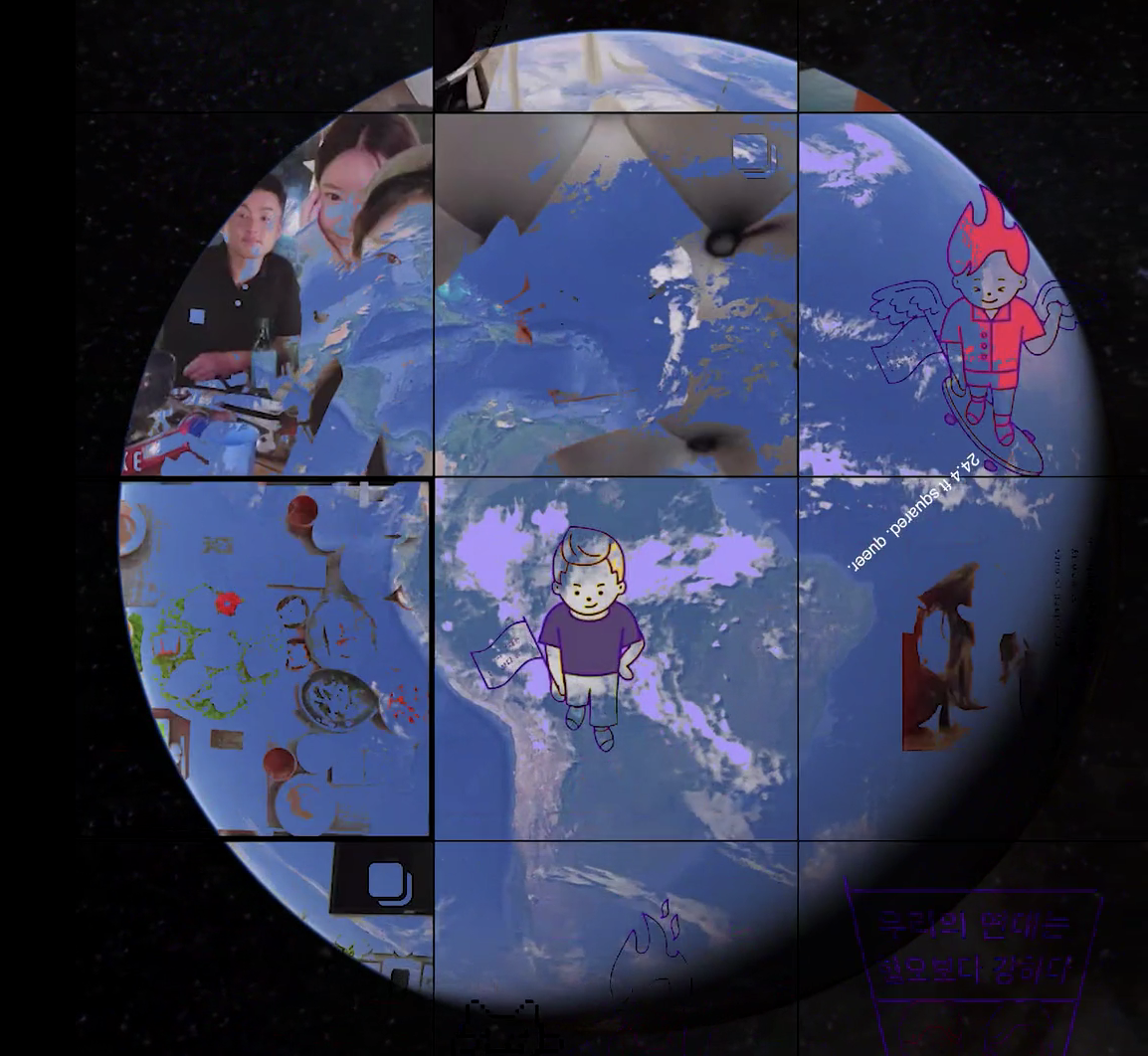

24.4 ft squared. queer.

(2020. video, 2:44)

코로나로 인해 열리지 못했던 2020 퀴어퍼레이드를 온라인으로 옮긴 운동 중 하나인 닷페이스의 '우리는 없던길도 만들지'를 기반으로 만들어진 작품으로 정치적으로 상징적인 시청 앞 광장을 점유하는 것을 통해 시민으로서 인정받으며 ‘시청께 허락 받은 퀴

어다‘, 등의 문구를 사용했던 과거를 톺아보며 퀴어들이 시민주체로서 인정받으려는 현상 자체에 대해 의문을 가진다. 또한 퀴어들이 가시화를 위해 노력함과 동시에 퍼레이드 등에서는 제한적으로 촬영을 허가하는등 아웃팅의 문제가 있었는데 온라인 퀴퍼는 그 아이러

니를 해소하며 개개인의 모임으로서 진정한 퀴어들을 퀴어들로서 존재하게 하고, 가시화된 기록으로 남을 수 있도록 한다.

11일 동안 85,767명에게 24,400 인스타그램 포스트를 통해 만들어진 이 운동은 24.4sq ft를 한 퀴어주체가 생활하는 공간으로 가정하고, 이러한 공간 자체의 확장이 아닌 공간들이 더해짐을 통해 더 큰 네모가 만들어지고 확장되는 공간을 그린다.

< 24.4 ft squared. queer (2020)> focuses on the online queer activism in Korea, where cyberspace provided alternative possibilities and extension of the previous limitations the queer festivals in Korea faced. As covid-19 swept the streets in 2020, queer festivals and parades were cancelled. Alternative media company dot.face organized a queer parade online, as a hashtag movement. “#we make a way out of nowhere(우리는 없던 길도 만들지)” was officially used by 85,767 people online for 11days, counting up to 24,400 posts on Instagram.

Seoul Queer Culture Festival is the biggest and the oldest queer parade in Korea, dating back to 2000. Just like its name, it was considered as a cultural event as well as a political parade that was held in different places every time, more like any place that was available for the queer population. In 2014, the parade was held in Sinchon and were physically blocked by the conservative Christians for 4 hours, while being verbally and physically abused in public space where the police were present. After such a traumatic event, the influence and presence of public recognition became unprecedentedly clear in queer politics as it emerged as a compromised solution to achieve political goals (Heo. 2019:23-24).

Along with the elevated social interest in minority rights, Seoul Queer Culture Festival conquered the Seoul plaza, where layers of history and political debated are embedded. Official slogans such as “city council permitted queer(시청께 허락받은 퀴어다)”, “yay- we were Seoul citizens(와- 우리도 서울 시민이다)” were posted with stickers, flags and online hashtags all over the plaza and online, as if approval from the government served any meaning. It was meaningful in the sense that political queer identities were available in the public space as a government-approved valid citizen. However, queer politics aim to confuse and disassemble heteronormativity.

Seoul plaza brings in the necessity to rely strongly on the judicial authority of the police force and council to guarantee the safety of participants. While citizenship discourse allows spaces for expansion of rights, it inevitably privatizes sexuality in terms of heteronormativity. Bringing queer persons into the public sphere as political individuals require anonymization of the public space also, for the safety of the participants. The queer individual must parade through the physical arena for queer visibility, but the queer person must be kept undocumented and unreproduced for the safety of the person. These compromises suggest that the “aim to visualize sexuality by occupying Seoul plaza is holding hands with the lust to be an approved queer citizen, rather than criticizing the separation and public and private spheres that limit certain sexualities in the hierarchy (Heo. 2019:28)”. By parading in the most politically meaningful place in Korea, the queer population is assimilating to heteronormativity.

So let’s bring it online.

Bringing the parade online loosens limitations and expands the possibility of solidarity. Online spaces have long been defined as a male-dominated territory where the pre-existing power hierarchy is enforced in the same way (Kendall 2002). However, power relations among gender differ according to the space dynamic. Since online spaces do not exactly reproduce the heteronormative reality but do not completely deviate from it, it must be viewed with a different scope (Kim, 2017:805).

The parade was flooded with hate organizations as well as just random people, just like the offline parade. The demography of hate organizations (or individuals) was very different though since they were mostly TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) organizations with the slogan ‘get the L(esbian) out’. Some posted with big red letters, while some disguised themselves as a participant while inserting a small phrase in the corner of the image. Some hate postings were done by the participants themselves for the ‘fun’ of replicating the actual space, posting conservative Christian postings, homophobic articles or slogans. Some random people just used this hashtag for whatever reason, posting irrelevant selfies and food pics. Oh, and of course, there were ice cream trucks, merch venues and freebies since it was in the middle of June and why not. Hashtag activism reclaims the voices of the minority in the public space while efficiently reframing the personal narrative into individual narratives to be united under a single name through repetition (Eagle, 2015; Clark, 2016). In the 2020 online queer parade, the participants could customize their own character’s looks, the flag, the surroundings, add features like wheelchairs, pets and so on. Some went further to add their design outside the given customization. People could express their identity inside one square while being flooded in the parade as a part of the movement. Here, the “entrenched division of labour between producers and audience”(Couldry 2003, 45) is blurred, as the producer becomes the audience and vice versa. Their narratives were told as much as they wanted to and hidden as much as they wanted to. This efficiently displays queer existence while deviating from the police force, council authorities to protect and permit the participants. It also allows unlimited documentation, resolving the paradox of limited visibility. Individuals were political subjects that reconstruct heteronormativity by resisting existing patriarchal discourses and visualizing the lived experiences of the minority in that feed (Kim, 2017).

< 24.4 ft squared. queer (2020)> extracts images from the 2020 online queer parade as well as found footages of the real world to blur the lines of the ‘virtual square’, where the personal experience is rendered as an individual experience. By suggesting the concept of a virtual square instead of a virtual space, it eliminated the underlying suggestion of unlimitedness and expansion in the word ‘space’ and focuses on the specific square of transformation.

Instead of expanding, it adds the political individual within the square to the larger square - the feed, to the larger square - the plaza, then to wherever the expansion is necessary. Without outstretching and wearing out a person for political aims, it relocates grouped individuals into pre-coded squares to question heteronormativity without having to compensate on the safety.

However, it also stamps on the malleable ground of virtu

al square, where coincidental yet inevitable crashings are highly unlikely to happen. If one does not search for the hashtag or blocks the hashtag, the hashtag remains silent and becomes a happy partitioned party.

Bibliography

Clark, Rosemary. 2016. “‘Hope in a Hashtag’: The Discursive Activism of #WhyIStayed.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (5): 788–804.

Couldry, Nick. 2003. Beyond the Hall of Mirrors? Some Theoretical Reflections on the Global Contestation of Media Power. In N. Couldry and J. Curran (eds.), Contesting Media Power: Alternative Media in a Networked World, 39-54. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Eagle, Ryan Bowles. 2015. “Loitering, Lingering, Hashtagging: Women Reclaiming Public Space Via #BoardtheBus, #StopStreetHarassment, and the #EverydaySexism Project.” Feminist Media Studies 15 (2): 350–353.

Harcourt, Wendy. 2000. Women’s Empowerment through the Internet. Asian Women 10, 19-31.

Kendall, Lori. 2002. Hanging Out in the Virtual Pub: Masculinities and Relationships Online. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kim, Tae-hyun. 2002. Internet Empowers Korean Social Movements. In D. Demers (ed.), Global News Media Reader, 235-248. Spokane, WA: Marquette Books.

Kim, Young-hee. 2002. Progressive Feminist Theories: A Reappraisal. Feminism Studies (Dongnyuk, Seoul) 2, 11-42

Jinsook Kim. 2017. #iamafeminist as the “mother tag”: feminist identification and activism against misogyny on Twitter in South Korea, Feminist Media Studies, 17:5, 804-820

Heo, Sung-Won .2019. 정치를 새롭게 읽어내는 퀴어정동정치: 한국 퀴어퍼레이드를 중심으로. 문화와 사회, 27(3), 7-48